info@graf.cat

GRAF, the platform that brings together contemporary art organisations to create a community.

Subscribe to receive the GRAF Newsletter, "here"

What is proposed next is an Olympic race. It is a race you can do on foot, in a calm way and without getting too tired, so in a way it is also a route. Our circuit can be completed in less than ten minutes and covers an exact kilometre. It also allows us to visit four essential sites in the history of The Olympic Chimera, a research and dissemination project framed in the context of Pormishuevismo (Formyballs-ism), a false artistic movement that has marked the history of architecture, urbanism and civil engineering in this country based “on cocks’ hitting the table”.

1) First stop: Olympic stadium Lluís Companys.

Architects: Vittorio Gregotti + Federico Correa and Alfonso Milà.

Refurbishment: 1985-1989.

To meet the Olympic date, the 1929 World’s Fair stadium had to be rehabilitated and its capacity increased. Vittorio, Federico and Alfonso’s project respects the stadium’s Noucentista vibe. The three architects agreed to lower the level of the track to gain grandstands and to be able to accommodate the 60,000 people required by the International Olympic Committee. The coincidences end there. They did not agree on how to order the stadium and ended up deciding for a mixed solution. The upper tiers are arranged as the Italian wished and the lower ones as the Catalans wished. It was rushed and unfinished to host the 1989 World Cup Athletics. It wasn’t a good day. After the rain, the leaks appeared and after the pro-independence boos against the King, the first doubts about the organizational capacity of Barcelona.

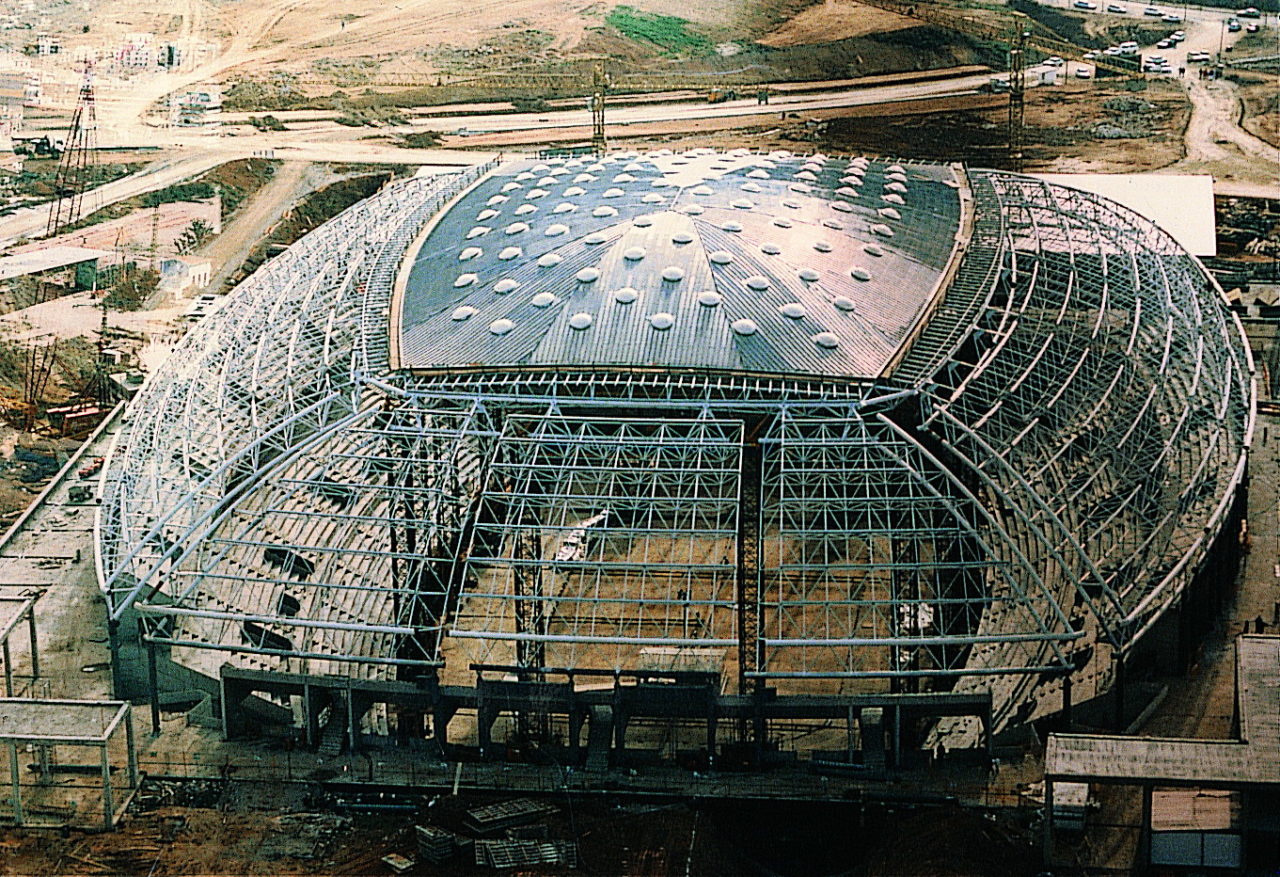

2) Second stop: Palau Sant Jordi.

Architect: Arata Isozaki.

Construction: 1983-1990.

For the city to host the Games, the IOC’s demands were clear. Barcelona had to build a sports hall with a capacity for 17,000 attendees that would be suitable for any track sport. Almost nothing. Isozaki’s project presented a spectacular roof of irregular undulations that evoked marine surfaces and Gaudinian languages. It’s a shame because it has nothing to do with what you’re seeing. The Gaudinian ripples ended up becoming the shell of a metal tortoise.

How did that happen? Nothing, silly things. It had been projected onto a landfill more than 40 meters deep. The change of location made the already hasty schedule of the work, to adopt a dizzying pace. But Isozaki did not complain. The Japanese redefined the building to place it a little further and changed the roof so that it could be mounted on the ground and raised with a revolutionary hydraulic jacking system that had only been tested once in history. Something much more performative than necessary.

On top of that, the pergola designed by Correa and Milà was incorporated into the building. Isozaki is, strangely, a very understanding Leo. In exchange for his “disinterested” understanding, his wife Aiko Miyawaki was commissioned with an art installation called “Utsurohi” (Change) consisting of 36 artificial stone columns scattered throughout the Olympic Ring.

3) Third stop: INEFC.

Architect: Ricardo Bofill.

Construction: 1988-1990.

The National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia (INEFC) really should not be where it is. The “Sports University” was designed to occupy the space in which it is now located Isozaki’s Palau de Sant Jordi.

Ricardo Bofill was extremely offended to see his building displaced and refused to cooperate. Those responsible for the ordination, asked him to touch up the project. It would have been enough for him to do the same as Isozaki and to harmonize it with the pergola they had designed. Bofill decided to take revenge. He displaced the building but did not turn it around. That is why the main access of INFEC is now outside the complex. Something that can be read as if Bofill was a sulky building that decides to turn its back on the rest of the group.

4) Fourth stop: The Telecommunications Antenna of Montjuïc.

Architect: Santiago Calatrava.

Construction: 1989-1992.

In Montjuïc there were two small antennas used by Telefónica whose usufruct contracts expired in 1990. Although the telephone company tried to renew them on several occasions, the City Council put up a lot of difficulties.

A legend says that one day Pascual Maragall called the telephone company and made them understand that if they wanted an antenna in Monjuïc for the Games, they would have to give it to Calatrava. Price of the phone prank? A little tower budgeted at 300 million pesetas, converted in less than three years into a tower of 3,000 million. That is, from 1.8 million euros to a crazy 18 million euros in a white sculpture with antennas.

Our short race ends here, in an oversized sculpture, a “Formyballs” landmark that, by the way, works as a sundial. The rest of the story you already know. Montserrat Caballé singing, more than 10,000 athletes walking through the city, a lot of volunteers shouting “hola” to the world, an archer, an arrow and a burning cauldron.

But if you want to know how it all started, you will have to open Instagram, search @preferiria.periferia and read ‘The Olympic Chimera’, the thirty-ninth chapter of Pormishuevism (Formyballs-ism). Are you ready? Ready? Now!

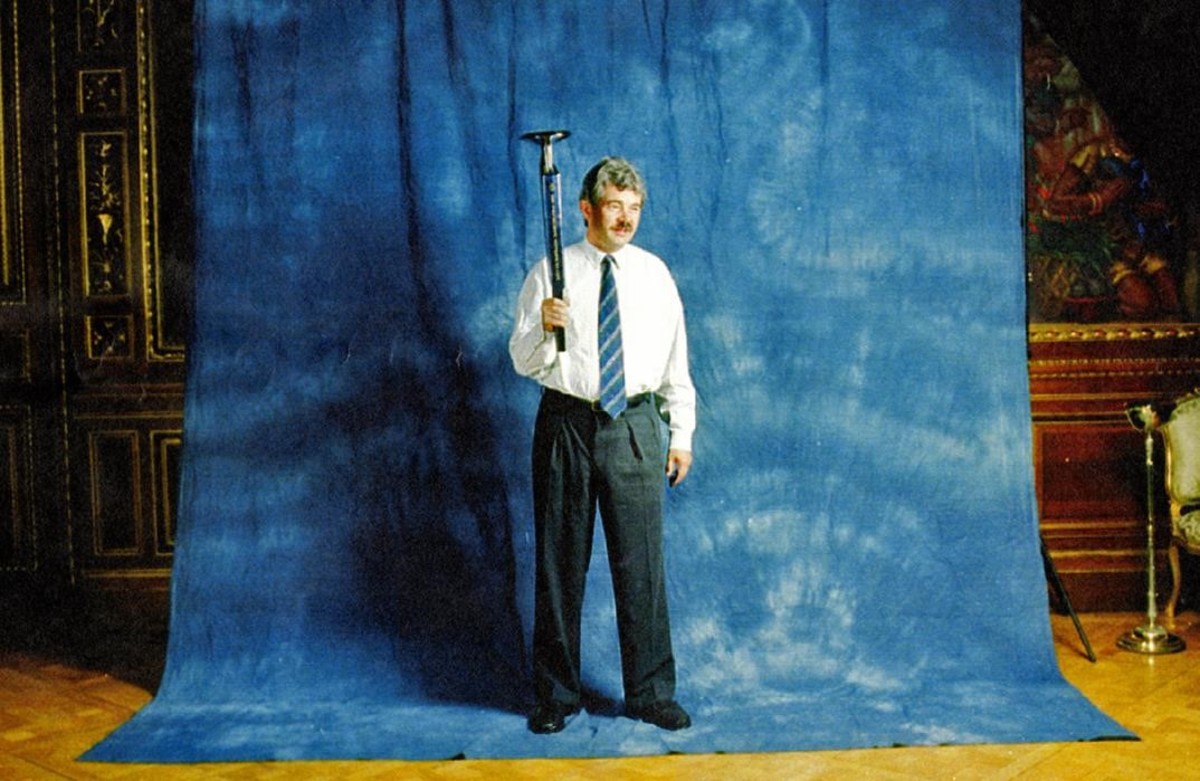

OLYMPIC GAMES ARCHIVE BARCELONA 92 PASQUAL MARAGALL MAYOR OF BARCELONA FOUR DAYS BEFORE THE OPENING OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES

–

Text by Erik Harley for GRAF. Harley is a visual artist expert in urban studies and resident at Bar Project.

Extract from ‘La Quimera Olímpica’ a research and dissemination project developed in Bar Project (Barcelona, 2020).